Notable Mardi Gras Absences Reflect Loss of Black Middle Class

By Julia Cass

Special to The Washington Post

Saturday, February 25, 2006; A01

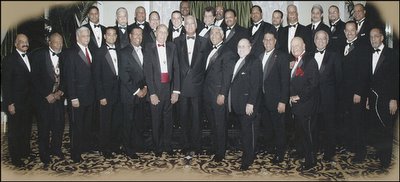

The Bunch Club, a group of African African professionals that has sponsored a Mardi Gras dance since 1917, in the last group photo taken at a black-tie dinner 71/2 months before Hurricane Katrina hit. (By Lloyd Dennis -- Courtesy Of Bunch Club)

The Bunch Club, a group of African African professionals that has sponsored a Mardi Gras dance since 1917, in the last group photo taken at a black-tie dinner 71/2 months before Hurricane Katrina hit. (By Lloyd Dennis -- Courtesy Of Bunch Club)Photo Credit: By Lloyd Dennis -- Courtesy Of Bunch Club

NEW ORLEANS -- Since 1917, the Bunch, an African American social club made up of 50 doctors, lawyers, dentists, bankers, businessmen and other professional men, has sponsored a dance on the Friday before Mardi Gras -- a coveted invitation during the weeks of parties that precede Fat Tuesday.

But last night there was no Bunch Club dance. The Black Pirates, Plantation Revelers, Bon Temps, Vikings, Beau Brummels, Original Illinois Club and Young Men's Illinois Club have also canceled their carnival balls.

The lack of revelry reflects the lack of people -- New Orleans's black middle class is gone.

Many African Americans prosperous enough to pay dues to a social club and buy tuxedos and gowns for debutante balls lived in the predominantly black subdivisions of New Orleans East, a former marshland drained by canals that severely flooded after Hurricane Katrina. Mile after mile of suburban homes along its cul-de-sacs and man-made lakes as well as a similar neighborhood, Gentilly, are virtually empty.

"The impression is that just poor people were displaced, but Katrina has had a devastating effect on the black middle class, too," said Willard Dumas, a dentist who serves as the Bunch Club's recording secretary and now lives in Baton Rouge. "You spend 45 years building a life and then it's gone. Your home was flooded; your business was flooded. And this happened not only to you but to practically everyone you know, so your patients or clients are gone, your friends are scattered, and your relatives are somewhere else."

White groups are holding their events this month, and debutante pictures are filling the society pages. The difference for the black groups can be explained by geography: Wealthy white neighborhoods were mostly on high ground, but black neighborhoods both poor and rich were on lowland that flooded.

Those black professionals are scattered across the South, finding new jobs, establishing new medical and legal practices and businesses. The longer they are gone, the greater the worry that they will not come back -- leaving New Orleans, a majority-black city before Katrina, without a core of African American leadership.

"We are a productive group of people," said lawyer Bernard Charbonnet Jr., 54, whose home was flooded. "We are the teachers, lawyers, firemen, doctors; the people who get up every morning and go to work; the people who have missions, goals and purposes; the people who serve on boards of civic organizations."

The Bunch Club personified that leadership as well as the longevity of blacks here. Some of its members have ancestral ties to the nearly 11,000 free blacks in New Orleans during the Civil War. The club began as a "bunch" of friends who gathered to play cards and decided to hold an annual carnival dance to meet women.

During the many years that hotels would not host African American events, the dance was held in the gym of Xavier University, the nation's only historically black Catholic university. More recently, the club has rented hotel ballrooms for the dance, which features a live orchestra and a march at midnight for the members and their guests.

In addition, the club's monthly meetings -- held at the now-closed Dooky Chase, a 65-year-old black-owned restaurant famous for its Creole food -- provided a chance to network. These days the group includes some of the city's most accomplished and influential African Americans, including Alden McDonald Jr., founder of Liberty Bank and Trust, the city's largest black-owned bank, and Xavier President Norman Francis, who is now chairman of the Louisiana Recovery Authority.

Charbonnet and Francis are still in New Orleans, but most of the rest of the Bunch are gone. Of the 44 members living in New Orleans before Katrina, only eight lived in houses that were not flooded and are inhabitable.

"The professionals who served the black population probably were the most impacted because they lost not just their homes but their clientele," said Francis, noting that 5,000 schoolteachers and 3,000 city employees, many of them black, have been laid off. "They are no different in a way from those families lower on the economic scale. They, too, don't have a home or a job."

Just two of the Bunch's doctors -- who were attached to hospitals on high ground -- practice in New Orleans today. White doctors, lawyers and other professionals also are experiencing difficulties, but proportionately more of their clients have returned.

Louis Bevrotte, the Bunch president, exemplifies the doctors' situation. Before the storm, he and his wife lived in the Lake Forest Estates subdivision in New Orleans East in a 4,700-square-foot home with a deck overlooking a man-made lake. McDonald, the bank president, lived across the street.

The East's 33 square miles of mostly single-family homes, developed in the 1970s and 1980s, became the "Freedomland," as one Bunch member put it, for African Americans of means. Bevrotte's office was a five-minute drive away, and he practiced at Methodist Hospital, one of two hospitals in the East, both now closed. He was so rooted in New Orleans that he did not have long-distance telephone service: his friends, his three children and other family members all lived in the city.

Now, Bevrotte, a pediatrician, practices in Kinder, La., population 2,000, about 220 miles west of New Orleans. In New Orleans, Bevrotte said, 95 percent of his patients were black; now, 95 percent are white. His wife, Yolanda, a nurse, works with him.

"We went through some rough times. We weren't used to having our lives out of our control," said Bevrotte, 60.

The worst part, he and his wife said, is being separated from their children and grandchildren, who live in Houston, Dallas and St. Francisville, La. "We cried when we separated six weeks after the storm and knew we would not see them the next day," Yolanda said.

The Bunch's dentists are experiencing the same dislocation. One is working in a prison near Jacksonville, Fla.; another moved to Louisville. The part-owner of a flooded professional building of black dentists and doctors, Dumas, 63, now works three days a week in a practice in a Baton Rouge suburb owned by a young dentist who had once worked for him.

Farrell Christophe, a former president of the Bunch, owns a five-bedroom house in Pontchartrain Park, the first black suburban-style subdivision in New Orleans, built 50 years ago. The home was flooded, and Christophe, 61, is living in Cane River, La.

He and his wife own three Steak Escape fast-food franchises in New Orleans. Two remain closed. Christophe fears he will have to walk away from them, because he thinks they are no longer viable businesses for him or a potential buyer.

"We aren't destitute, but our whole livelihood has changed," he said. "We don't know what we'll be doing six months from now. You might think: 'What's the matter with you?' You're both businesspeople, fairly intelligent. You should have plans.' But right now we don't know."

Those few Bunch members still in New Orleans with work and intact homes have lost their social network.

Keith Weldon Medley, 56, a writer who specializes in black New Orleans history, is the club's historian. He lives in the Marigny neighborhood, a part of the original crescent built in part by African American brick masons, carpenters and plasterers. Although he considers himself fortunate, he is not happy. Few of his family or friends are in the city anymore, and the tours he gives of New Orleans distress him because so many historic places, representing 300 years of black achievement, are damaged and closed, as are the schools he attended and the black-owned restaurants he liked.

"Life in New Orleans right now can be inexpressibly sad," he said.

Bunch members still return to New Orleans to meet insurance adjusters and gut homes. Many have complained that Mayor C. Ray Nagin's rebuilding commission turned its back on blacks when it called for a smaller city and turning neighborhoods like New Orleans East into green space. That plan is uncertain, but so are the new elevations the Federal Emergency Management Agency will require for rebuilding in flooded areas and where the financially strapped city will be able to provide police, fire and other services.

How many Bunch members and other black professionals will return is another unknown. Most said they want to come back.

Charles Bowers, 32, a doctor finishing his residency this spring in a hospital just outside New Orleans, said that his father and grandfather practiced medicine in the city and "I want to do the same. That was the plan. Now I'm weighing my options. I don't know."

© 2006 The Washington Post Company

No comments:

Post a Comment