Thursday, December 29, 2011

Friday, December 23, 2011

Finale of the Legendary 1978 Star Wars Holiday special

This was broadcast once in late November 1978 and then buried ever since.

Already weakened by the 1977 music tracks "Disco Duck" and "Star Wars Disco" and a bloated, lyric-forgetting drug-addicted Elvis' 1977 TV special, this broadcast almost tore the fabric of space-time and opened a black hole. It was like a cultural Cuban Missile Crisis; we came that close.

Already weakened by the 1977 music tracks "Disco Duck" and "Star Wars Disco" and a bloated, lyric-forgetting drug-addicted Elvis' 1977 TV special, this broadcast almost tore the fabric of space-time and opened a black hole. It was like a cultural Cuban Missile Crisis; we came that close.

Thursday, December 22, 2011

Monday, December 12, 2011

Great NYT Essay on New Music Scene: Club Kids Are Storming Music Museums

Read it HERE in the New York Times

December 9, 2011

Club Kids Are Storming Music Museums

By ALLAN KOZINN

WE critics have long argued vehemently that if major musical institutions hope to be regarded as vital, modern institutions, they must keep their listeners (and performers) in touch with the ideas, trendy or otherwise, that excite the composers of their time. But truth be told, we are a little bipolar on that subject. Though we criticize the big organizations for fostering a museum culture, we actually value the museums they have become.

Our attitude toward the classical canon, after all — and this increasingly applies also to older forms of jazz and pop — is that great music transcends time. If the New York Philharmonic did not regularly give us Beethoven, Brahms and symphonies, we would complain that it had abandoned the conservationist aspect of its charter and lament the disappearance of works that had moved people for decades or centuries.

That tension is not easily resolved. Even a model in which orchestras, chamber groups and opera companies present themselves as museums with substantial contemporary wings has almost insurmountable limitations circumscribing the possibility of hearing much new music. Consider that within the last 50 years Mahler, Shostakovich, Bartok, Sibelius and Copland have all moved from the periphery of the orchestral canon to its center, yet Beethoven, Brahms and company have not fallen out of fashion; and Bach, Haydn and Mozart, long ceded to period-instrument bands, are returning to the modern orchestra repertory. All this at a time when the world of young, inventive and often populist composers is exploding.

These young composers may hold the key to classical music’s future, and the future they create might not be what you expect. Increasingly they have come to consider the machinations of the big-ticket musical organizations — and debates about how to get them to accommodate new music — as beside the point.

Instead of waiting for established ensembles to give them a hearing, they have built an alternative musical universe. Its complex ecology and hierarchy of coolness includes webs of composer-performer collaborations, circuits of preferred concert spaces and an expanding number of record labels: among them, New Amsterdam, Cantaloupe and Tzadik, all composer run and stylistically freewheeling.

This world is centered in New York, though it has counterparts elsewhere. (Reykjavik, Iceland, seems unusually influential at the moment.) It thrives in concert spaces that make a point of informality. Some, like Le Poisson Rouge and the Cornelia Street Café in Greenwich Village and Galapagos in Brooklyn, are like jazz clubs: you can nurse a drink while listening to a performance, but the atmosphere is quiet and focused. Others are hole-in-the-wall funky: on summer nights at the Stone, in the East Village, performers debate whether to turn on a noisy fan or stifle with their listeners. Lately new-music haunts like the Issue Project Room and Roulette have found larger spaces (both in Brooklyn) and the money to pay for them.

Just as crucial, emerging composers have built an enthusiastic, growing audience that, while mostly young, is expanding across age and demographic lines. Perhaps because the music these composers produce is wildly eclectic, dogma free and more likely to have undercurrents of humor than doctrinaire earnestness, it is attracting older music fans who, it turns out, were seeking composers to champion all along but were left cold by the harshness of the serialists and bored by the repetitiveness of the minimalists, and found too few havens between those extremes.

It would be wrong to suggest that the young composers who have created this burgeoning alternative world have no interest in the big institutions. Nor do they disdain the standard repertory. Most would love to have their works performed by major orchestras, and some get lucky: Anna Clyne and Mason Bates were appointed composers in residence at the Chicago Symphony; Nico Muhly will have a work performed at the Metropolitan Opera.

But they have other models too. They attended conservatories and went through the same rigorous training as their predecessors, but they have not inherited their teachers’ battles. For them serialism and Minimalism are equally useful tools in a gestural language that draws on rock, jazz, hip-hop, world music and every reconfiguration of classical language from medieval times through Romanticism. And though there was a time when classical-music students played little but classical music, these musicians have played it all. Today you can hardly find a composer under 40 who did not play in rock bands as a teenager.

Some still have them, but now they include orchestral instruments and computers alongside electric guitars and basses, drums and electronic keyboards. In all this music the timbres, the textures and, often, the energy are those of rock, but the structures, substance and time scales are rooted in classical music. Electric guitars may simmer or wail, and drums may pound, but this is not the stuff of pop hits. When you listen to the Now Ensemble or the amplified, heavily processed string quartet Ethel or groups led by the composers Missy Mazzoli, Du Yun, Judd Greenstein, Caleb Burhans or Bryce Dessner, you inevitably wonder whether you’re hearing a rock band or a chamber group, and whether it matters.

A polished composer like Jefferson Friedman can have it both ways. Having poured his stylistically wide-ranging thoughts into his string quartets, he happily allowed the electronica group Matmos to remix them, adding beats and other sounds, and cutting and pasting musical lines. Several of these composers have the D.J.-remix-mash-up culture of post-1980s pop in their blood.

This scene was not suddenly created from nothing. If you pick at its fabric, you will find strands stretching back to the late 1960s, when Minimalists and avant-gardists began forming bands and giving loft concerts, and when European art-rock bands like Tangerine Dream, Gong, Faust and Henry Cow began exploring unusual (for rock) meters, harmonies, textures and structures.

You see its origins in the late 1970s, when the Kronos Quartet began its long, iconoclastic run in San Francisco, while in New York, Rhys Chatham began writing serious pieces for electric guitars, and Glenn Branca became better known for his guitar symphonies than for his work with his No Wave rock band, the Theoretical Girls. Its early rumblings inspired a blossoming of lively avant-garde festivals in the late 1980s and early 1990s: among them, the composer-run Bang on a Can and MATA festivals, as well as Next Wave at the Brooklyn Academy of Music and Serious Fun! at Lincoln Center.

This movement — still nameless, though it is sometimes called alt-classical — has really reached critical mass only in the last five years or so. Its economic muscle remains untested: packing a few hundred listeners into a club is one thing, but could that audience fill Avery Fisher Hall night after night? Does it want to? Part of this world’s charm, after all, is its intimacy and informality, and its inexpensive tickets.

Yet when Carnegie Hall has presented concerts aimed at this crowd’s tastes, usually in the small but technologically up-to-date Zankel Hall, the seats have been filled. Seats were also filled when Alarm Will Sound and other groups played at Alice Tully Hall recently and when Adrian Utley, of the British band Portishead, and Will Gregory, of the electronica duo Goldfrapp, performed a new chamber-rock film score for Carl Theodor Dreyer’s “Passion de Jeanne d’Arc” as part of the White Light Festival last month, in the same hall.

That Lincoln Center and Carnegie Hall are hoping to tap this market suggests that the mainstream musical world sees its potential. So do the conventional classical ensembles (the Emerson Quartet, Orpheus) and soloists (the pianist Hélène Grimaud, the operatic tenor Joseph Calleja) who have recently migrated to clubs for record-release parties — a practice borrowed from the pop world by way of labels like New Amsterdam — or simply to trawl for a new audience.

The major institutions would no doubt love to tap into this world’s energy, audience and of-the-moment cachet. But to do so they would have to rethink their repertories, ticket prices and performance styles radically, and it seems unlikely that their existing audiences and donors would stand for that.

That said, some organizations have nothing to lose. New York City Opera, the Brooklyn Philharmonic and the American Composers Orchestra, all venerable institutions that have fallen on hard times, are experimenting with genre-crossing orchestras and seeking new performance spaces. Whether they survive will tell us a lot about the power of this new approach and what it can mean for classical music generally.

But it may mean nothing for classical music. Perhaps instead of being a shot in the arm, this movement will lead to an epochal splintering in which composers in the new style continue doing what they are doing now: making artistic choices that draw as much on nonclassical influences as on classical ones and writing for ensembles that use computers, amplification, sound processing and non-Western instruments. This world may break away from traditional classical music much the way jazz split from blues in the 1920s; rock blossomed from rhythm and blues, country and soul in the 1950s; and hip-hop arose from within pop in the 1980s.

There is no reason the two worlds could not remain porous. But in that case today’s orchestras would embrace their museum aspect wholeheartedly and become extensions of the period-instrument world, specializing in music written during the 19th and 20th centuries. Composers receiving their training now, and listening to jazz, rock, hip-hop and world music in their spare time, would write for new, amplified or partly electronic ensembles.

It is not a matter of whether this is a good development or a bad one; it is evolution in action. And if nothing else, it should afford a respite of several decades before we read hand-wringing reports about the graying of the Issue Project Room audience.

December 9, 2011

Club Kids Are Storming Music Museums

By ALLAN KOZINN

WE critics have long argued vehemently that if major musical institutions hope to be regarded as vital, modern institutions, they must keep their listeners (and performers) in touch with the ideas, trendy or otherwise, that excite the composers of their time. But truth be told, we are a little bipolar on that subject. Though we criticize the big organizations for fostering a museum culture, we actually value the museums they have become.

Our attitude toward the classical canon, after all — and this increasingly applies also to older forms of jazz and pop — is that great music transcends time. If the New York Philharmonic did not regularly give us Beethoven, Brahms and symphonies, we would complain that it had abandoned the conservationist aspect of its charter and lament the disappearance of works that had moved people for decades or centuries.

That tension is not easily resolved. Even a model in which orchestras, chamber groups and opera companies present themselves as museums with substantial contemporary wings has almost insurmountable limitations circumscribing the possibility of hearing much new music. Consider that within the last 50 years Mahler, Shostakovich, Bartok, Sibelius and Copland have all moved from the periphery of the orchestral canon to its center, yet Beethoven, Brahms and company have not fallen out of fashion; and Bach, Haydn and Mozart, long ceded to period-instrument bands, are returning to the modern orchestra repertory. All this at a time when the world of young, inventive and often populist composers is exploding.

These young composers may hold the key to classical music’s future, and the future they create might not be what you expect. Increasingly they have come to consider the machinations of the big-ticket musical organizations — and debates about how to get them to accommodate new music — as beside the point.

Instead of waiting for established ensembles to give them a hearing, they have built an alternative musical universe. Its complex ecology and hierarchy of coolness includes webs of composer-performer collaborations, circuits of preferred concert spaces and an expanding number of record labels: among them, New Amsterdam, Cantaloupe and Tzadik, all composer run and stylistically freewheeling.

This world is centered in New York, though it has counterparts elsewhere. (Reykjavik, Iceland, seems unusually influential at the moment.) It thrives in concert spaces that make a point of informality. Some, like Le Poisson Rouge and the Cornelia Street Café in Greenwich Village and Galapagos in Brooklyn, are like jazz clubs: you can nurse a drink while listening to a performance, but the atmosphere is quiet and focused. Others are hole-in-the-wall funky: on summer nights at the Stone, in the East Village, performers debate whether to turn on a noisy fan or stifle with their listeners. Lately new-music haunts like the Issue Project Room and Roulette have found larger spaces (both in Brooklyn) and the money to pay for them.

Just as crucial, emerging composers have built an enthusiastic, growing audience that, while mostly young, is expanding across age and demographic lines. Perhaps because the music these composers produce is wildly eclectic, dogma free and more likely to have undercurrents of humor than doctrinaire earnestness, it is attracting older music fans who, it turns out, were seeking composers to champion all along but were left cold by the harshness of the serialists and bored by the repetitiveness of the minimalists, and found too few havens between those extremes.

It would be wrong to suggest that the young composers who have created this burgeoning alternative world have no interest in the big institutions. Nor do they disdain the standard repertory. Most would love to have their works performed by major orchestras, and some get lucky: Anna Clyne and Mason Bates were appointed composers in residence at the Chicago Symphony; Nico Muhly will have a work performed at the Metropolitan Opera.

But they have other models too. They attended conservatories and went through the same rigorous training as their predecessors, but they have not inherited their teachers’ battles. For them serialism and Minimalism are equally useful tools in a gestural language that draws on rock, jazz, hip-hop, world music and every reconfiguration of classical language from medieval times through Romanticism. And though there was a time when classical-music students played little but classical music, these musicians have played it all. Today you can hardly find a composer under 40 who did not play in rock bands as a teenager.

Some still have them, but now they include orchestral instruments and computers alongside electric guitars and basses, drums and electronic keyboards. In all this music the timbres, the textures and, often, the energy are those of rock, but the structures, substance and time scales are rooted in classical music. Electric guitars may simmer or wail, and drums may pound, but this is not the stuff of pop hits. When you listen to the Now Ensemble or the amplified, heavily processed string quartet Ethel or groups led by the composers Missy Mazzoli, Du Yun, Judd Greenstein, Caleb Burhans or Bryce Dessner, you inevitably wonder whether you’re hearing a rock band or a chamber group, and whether it matters.

A polished composer like Jefferson Friedman can have it both ways. Having poured his stylistically wide-ranging thoughts into his string quartets, he happily allowed the electronica group Matmos to remix them, adding beats and other sounds, and cutting and pasting musical lines. Several of these composers have the D.J.-remix-mash-up culture of post-1980s pop in their blood.

This scene was not suddenly created from nothing. If you pick at its fabric, you will find strands stretching back to the late 1960s, when Minimalists and avant-gardists began forming bands and giving loft concerts, and when European art-rock bands like Tangerine Dream, Gong, Faust and Henry Cow began exploring unusual (for rock) meters, harmonies, textures and structures.

You see its origins in the late 1970s, when the Kronos Quartet began its long, iconoclastic run in San Francisco, while in New York, Rhys Chatham began writing serious pieces for electric guitars, and Glenn Branca became better known for his guitar symphonies than for his work with his No Wave rock band, the Theoretical Girls. Its early rumblings inspired a blossoming of lively avant-garde festivals in the late 1980s and early 1990s: among them, the composer-run Bang on a Can and MATA festivals, as well as Next Wave at the Brooklyn Academy of Music and Serious Fun! at Lincoln Center.

This movement — still nameless, though it is sometimes called alt-classical — has really reached critical mass only in the last five years or so. Its economic muscle remains untested: packing a few hundred listeners into a club is one thing, but could that audience fill Avery Fisher Hall night after night? Does it want to? Part of this world’s charm, after all, is its intimacy and informality, and its inexpensive tickets.

Yet when Carnegie Hall has presented concerts aimed at this crowd’s tastes, usually in the small but technologically up-to-date Zankel Hall, the seats have been filled. Seats were also filled when Alarm Will Sound and other groups played at Alice Tully Hall recently and when Adrian Utley, of the British band Portishead, and Will Gregory, of the electronica duo Goldfrapp, performed a new chamber-rock film score for Carl Theodor Dreyer’s “Passion de Jeanne d’Arc” as part of the White Light Festival last month, in the same hall.

That Lincoln Center and Carnegie Hall are hoping to tap this market suggests that the mainstream musical world sees its potential. So do the conventional classical ensembles (the Emerson Quartet, Orpheus) and soloists (the pianist Hélène Grimaud, the operatic tenor Joseph Calleja) who have recently migrated to clubs for record-release parties — a practice borrowed from the pop world by way of labels like New Amsterdam — or simply to trawl for a new audience.

The major institutions would no doubt love to tap into this world’s energy, audience and of-the-moment cachet. But to do so they would have to rethink their repertories, ticket prices and performance styles radically, and it seems unlikely that their existing audiences and donors would stand for that.

That said, some organizations have nothing to lose. New York City Opera, the Brooklyn Philharmonic and the American Composers Orchestra, all venerable institutions that have fallen on hard times, are experimenting with genre-crossing orchestras and seeking new performance spaces. Whether they survive will tell us a lot about the power of this new approach and what it can mean for classical music generally.

But it may mean nothing for classical music. Perhaps instead of being a shot in the arm, this movement will lead to an epochal splintering in which composers in the new style continue doing what they are doing now: making artistic choices that draw as much on nonclassical influences as on classical ones and writing for ensembles that use computers, amplification, sound processing and non-Western instruments. This world may break away from traditional classical music much the way jazz split from blues in the 1920s; rock blossomed from rhythm and blues, country and soul in the 1950s; and hip-hop arose from within pop in the 1980s.

There is no reason the two worlds could not remain porous. But in that case today’s orchestras would embrace their museum aspect wholeheartedly and become extensions of the period-instrument world, specializing in music written during the 19th and 20th centuries. Composers receiving their training now, and listening to jazz, rock, hip-hop and world music in their spare time, would write for new, amplified or partly electronic ensembles.

It is not a matter of whether this is a good development or a bad one; it is evolution in action. And if nothing else, it should afford a respite of several decades before we read hand-wringing reports about the graying of the Issue Project Room audience.

"Vocal Fry" Creeping into US Speech

Article in Science magazine, including an audio sample of this glottalization (a creaky sound that you've heard before). Check out the article and sample HERE.

Doesn't sound very new to me.

Doesn't sound very new to me.

Sunday, December 11, 2011

The Buddy Rich Bus Tapes

For many years these were an underground secret, secretly recorded in the early 80s (1983?) on the band bus while Buddy Rich chewed them out.

Saturday, December 10, 2011

Wednesday, November 23, 2011

Sunday, November 20, 2011

Saturday, November 19, 2011

Wednesday, November 02, 2011

Saturday, October 29, 2011

The Last Master of a Sikh Martial Art

BBC

29 October 2011 Last updated at 19:16 ET

The only living master of a dying martial art

By Stephanie Hegarty BBC World Service

A former factory worker from the British Midlands may be the last living master of the centuries-old Sikh battlefield art of shastar vidya. The father of four is now engaged in a full-time search for a successor.

The basis of shastar vidya, the "science of weapons" is a five-step movement: advance on the opponent, hit his flank, deflect incoming blows, take a commanding position and strike.

It was developed by Sikhs in the 17th Century as the young religion came under attack from hostile Muslim and Hindu neighbours, and has been known to a dwindling band since the British forced Sikhs to give up arms in the 19th Century.

Nidar Singh, a 44-year-old former food packer from Wolverhampton, is now thought to be the only remaining master. He has many students, but shastar vidya takes years to learn and a commitment in time and energy that doesn't suit modern lifestyles.

"I've travelled all over India and I have spoken to many elders, this is basically a last-ditch attempt to flush someone out because if I die with it, it is all gone."

He would be overjoyed to discover an existing master somewhere in India, or to find a talented young student determined to dedicate his life to the art.

Until he was 17 years old, he knew little of his Sikh heritage. His family were not religious - he wore his hair short and dressed like any British teenager. He was a keen wrestler, but knew nothing of martial arts.

He spent his childhood between Punjab and Wolverhampton and it was on one of these trips to see an aunt in India that he met Baba Mohinder Singh, the old man who was to become his master.

Already in his early 80s, Baba Mohinder Singh had abandoned life as a hermit in a final effort to find someone to pass on his knowledge to.

"When he saw my physique he looked at me, even though I was clean-shaven and he asked me: 'Do you want to learn how to fight'," recalls Nidar Singh. "I couldn't say no."

On his first day of training, the frail old man handed him a stick and instructed Mr Singh to hit him. When he tried, the master threw him around like a rag doll.

"He was a frail old man chucking me about and I couldn't touch him," he says. "That definitely impressed me."

Read the full story HERE.

Thursday, October 27, 2011

Wednesday, October 26, 2011

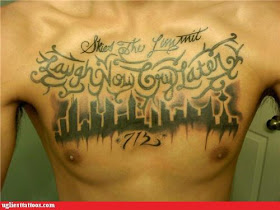

Misspelled Tattoos 6: Tattooing the Wrong Word

Yep, straight from the Fail Blog family of sites comes yet another of my periodic tributes to people stupid enough to have misspellings inked into their skin. This post is a slight twist on that theme: tattoos that use incorrect words. So even if life did come with a spellchecker, it still wouldn't catch using the wrong word.

Thine Own

...and another

Accept (not except)

[and this last one is the correct word but misspelled]

His Own, not Is Own

Sky's (not skies) and limit (not limmit)

than/then a part (should be two words) and everywhere (should be spelled correctly and one word)

I don't know what the hell is going on here. I blame tequila.

Thine Own

...and another

Accept (not except)

[and this last one is the correct word but misspelled]

His Own, not Is Own

Sky's (not skies) and limit (not limmit)

than/then a part (should be two words) and everywhere (should be spelled correctly and one word)

I don't know what the hell is going on here. I blame tequila.

China Preparing to Crack Down on Microblogs and Cultural Expression

NYT

October 26, 2011

China Cracks Down on Bloggers and ‘Excessive’ Entertainment

By SHARON LAFRANIERE, MICHAEL WINES and EDWARD WONG

BEIJING — Political censorship in this authoritarian state has long been heavy-handed. But for years, the Communist Party has tolerated a creeping liberalization in popular culture, tacitly allowing everything from popular knockoffs of “American Idol”-style talent shows to freewheeling microblogs that let media groups prosper and let people blow off steam.

Now, the party appears to be saying “enough.”

Whether spooked by popular uprisings worldwide, a coming leadership transition at home or their own citizens’ increasingly provocative tastes, Communist leaders are proposing new limits on media and Internet freedoms that include some of the most restrictive measures in years.

The most striking instance occurred Tuesday, when the State Administration of Radio, Film and Television ordered 34 major regional television stations to limit themselves to no more than two 90-minute entertainment shows each per week, and collectively 10 nationwide. They are also being ordered to broadcast two hours of state-approved news every evening and to disregard audience ratings in their programming decisions. The ministry said the measures, to go into effect on Jan. 1, were aimed at rooting out “excessive entertainment and vulgar tendencies.”

The restrictions arrived as party leaders signaled new curbs on China’s short-message, Twitter-like microblogs, an Internet sensation that has mushroomed in less than two years into a major — and difficult to control — source of whistle-blowing. Microbloggers, some of whom have attracted millions of followers, have been exposing scandals and official malfeasance, including an attempted cover-up of a recent high-speed rail accident, with astonishing speed and popularity.

On Wednesday, the Communist Party’s Central Committee called in a report on its annual meeting for an “Internet management system” that would strictly regulate social network and instant-message systems, and punish those who spread “harmful information.” The focus of the meeting, held this month, was on culture and ideology.

Analysts and employees inside the private companies that manage the microblogs say party officials are pressing for increasingly strict and swift censorship of unapproved opinions. Perhaps most telling, the authorities are discussing requiring microbloggers to register accounts with their real names and identification numbers instead of the anonymous handles now in wide use.

Although China’s most famous bloggers tend to use their own names, requiring everyone to do so would make online whistle-blowing and criticism of officialdom — two public services not easily duplicated elsewhere — considerably riskier.

It would “definitely be harmful to free speech,” said one microblog editor who refused to be named for fear of reprisal.

This newly buttoned-down approach coincides with a planned shift in the top leadership of the ruling party and government, an intricate process that will last for the next year. During such a period, tolerance for outspokenness outside official channels tends to shrink, and bureaucrats eager for promotion show their conservative stripes.

The crackdown also follows popular uprisings across the Middle East that appear to have given China’s leaders pause regarding their own hold on absolute power. In the view of some, it also tracks the influence in China’s ruling hierarchy of hard-liners like Zhou Yongkang, the public security chief who helped preside over the suppression of riots by ethnic Uighurs in western China’s Xinjiang region.

On Tuesday, Xinhua, the state news agency, reported that Mr. Zhou was urging authorities “to solve problems regarding social integrity, morality and Internet management” and that he had called for “the early introduction of laws and regulations on the management of the Internet,” among other things.

Nobody outside China’s closeted leadership knows the true reason for the maneuvers, beyond a general and intangible sense of uneasiness over the degree to which freer speech is taking root here. The microblogs, or weibos, are perhaps the prime example.

Read the full post HERE.

October 26, 2011

China Cracks Down on Bloggers and ‘Excessive’ Entertainment

By SHARON LAFRANIERE, MICHAEL WINES and EDWARD WONG

BEIJING — Political censorship in this authoritarian state has long been heavy-handed. But for years, the Communist Party has tolerated a creeping liberalization in popular culture, tacitly allowing everything from popular knockoffs of “American Idol”-style talent shows to freewheeling microblogs that let media groups prosper and let people blow off steam.

Now, the party appears to be saying “enough.”

Whether spooked by popular uprisings worldwide, a coming leadership transition at home or their own citizens’ increasingly provocative tastes, Communist leaders are proposing new limits on media and Internet freedoms that include some of the most restrictive measures in years.

The most striking instance occurred Tuesday, when the State Administration of Radio, Film and Television ordered 34 major regional television stations to limit themselves to no more than two 90-minute entertainment shows each per week, and collectively 10 nationwide. They are also being ordered to broadcast two hours of state-approved news every evening and to disregard audience ratings in their programming decisions. The ministry said the measures, to go into effect on Jan. 1, were aimed at rooting out “excessive entertainment and vulgar tendencies.”

The restrictions arrived as party leaders signaled new curbs on China’s short-message, Twitter-like microblogs, an Internet sensation that has mushroomed in less than two years into a major — and difficult to control — source of whistle-blowing. Microbloggers, some of whom have attracted millions of followers, have been exposing scandals and official malfeasance, including an attempted cover-up of a recent high-speed rail accident, with astonishing speed and popularity.

On Wednesday, the Communist Party’s Central Committee called in a report on its annual meeting for an “Internet management system” that would strictly regulate social network and instant-message systems, and punish those who spread “harmful information.” The focus of the meeting, held this month, was on culture and ideology.

Analysts and employees inside the private companies that manage the microblogs say party officials are pressing for increasingly strict and swift censorship of unapproved opinions. Perhaps most telling, the authorities are discussing requiring microbloggers to register accounts with their real names and identification numbers instead of the anonymous handles now in wide use.

Although China’s most famous bloggers tend to use their own names, requiring everyone to do so would make online whistle-blowing and criticism of officialdom — two public services not easily duplicated elsewhere — considerably riskier.

It would “definitely be harmful to free speech,” said one microblog editor who refused to be named for fear of reprisal.

This newly buttoned-down approach coincides with a planned shift in the top leadership of the ruling party and government, an intricate process that will last for the next year. During such a period, tolerance for outspokenness outside official channels tends to shrink, and bureaucrats eager for promotion show their conservative stripes.

The crackdown also follows popular uprisings across the Middle East that appear to have given China’s leaders pause regarding their own hold on absolute power. In the view of some, it also tracks the influence in China’s ruling hierarchy of hard-liners like Zhou Yongkang, the public security chief who helped preside over the suppression of riots by ethnic Uighurs in western China’s Xinjiang region.

On Tuesday, Xinhua, the state news agency, reported that Mr. Zhou was urging authorities “to solve problems regarding social integrity, morality and Internet management” and that he had called for “the early introduction of laws and regulations on the management of the Internet,” among other things.

Nobody outside China’s closeted leadership knows the true reason for the maneuvers, beyond a general and intangible sense of uneasiness over the degree to which freer speech is taking root here. The microblogs, or weibos, are perhaps the prime example.

Read the full post HERE.

Zooey Deschanel's Performance of the National Anthem at the World Series10/23/11

I was traveling and didn't see it live, but I was surprised that certain right-wing pundits were criticizing her performance as being not "triumphant" enough. When there are too many melismas people criticize the anthem, and now this very moving and understated version apparently isn't the musical equivalent of a big foam "We're #1" hand. I think it is nice and really gets to the ethos of the song while putting the emphasis on the anthem's subject matter more than the performer. Link from MLB with an ad up front:

Tuesday, October 25, 2011

Monday, October 17, 2011

Tuesday, October 11, 2011

Sunday, October 09, 2011

Daughter of ‘Dirty War,’ Raised by Man Who Killed Her Parents

One of the many horrible stories of Argentina's "Dirty War."

NYT

October 8, 2011

Daughter of ‘Dirty War,’ Raised by Man Who Killed Her Parents

By ALEXEI BARRIONUEVO

BUENOS AIRES — Victoria Montenegro recalls a childhood filled with chilling dinnertime discussions. Lt. Col. Hernán Tetzlaff, the head of the family, would recount military operations he had taken part in where “subversives” had been tortured or killed. The discussions often ended with his “slamming his gun on the table,” she said.

It took an incessant search by a human rights group, a DNA match and almost a decade of overcoming denial for Ms. Montenegro, 35, to realize that Colonel Tetzlaff was, in fact, not her father — nor the hero he portrayed himself to be.

Instead, he was the man responsible for murdering her real parents and illegally taking her as his own child, she said.

He confessed to her what he had done in 2000, Ms. Montenegro said. But it was not until she testified at a trial here last spring that she finally came to grips with her past, shedding once and for all the name that Colonel Tetzlaff and his wife had given her — María Sol — after falsifying her birth records.

The trial, in the final phase of hearing testimony, could prove for the first time that the nation’s top military leaders engaged in a systematic plan to steal babies from perceived enemies of the government.

Jorge Rafael Videla, who led the military during Argentina’s dictatorship, stands accused of leading the effort to take babies from mothers in clandestine detention centers and give them to military or security officials, or even to third parties, on the condition that the new parents hide the true identities. Mr. Videla is one of 11 officials on trial for 35 acts of illegal appropriation of minors.

The trial is also revealing the complicity of civilians, including judges and officials of the Roman Catholic Church.

The abduction of an estimated 500 babies was one of the most traumatic chapters of the military dictatorship that ruled Argentina from 1976 to 1983. The frantic effort by mothers and grandmothers to locate their missing children has never let up. It was the one issue that civilian presidents elected after 1983 did not excuse the military for, even as amnesty was granted for other “dirty war” crimes.

“Even the many Argentines who considered the amnesty a necessary evil were unwilling to forgive the military for this,” said José Miguel Vivanco, the Americas director for Human Rights Watch.

In Latin America, the baby thefts were largely unique to Argentina’s dictatorship, Mr. Vivanco said. There was no such effort in neighboring Chile’s 17-year dictatorship.

One notable difference was the role of the Catholic Church. In Argentina the church largely supported the military government, while in Chile it confronted the government of Gen. Augusto Pinochet and sought to expose its human rights crimes, Mr. Vivanco said.

Priests and bishops in Argentina justified their support of the government on national security concerns, and defended the taking of children as a way to ensure they were not “contaminated” by leftist enemies of the military, said Adolfo Pérez Esquivel, a Nobel Prize-winning human rights advocate who has investigated dozens of disappearances and testified at the trial last month.

Ms. Montenegro contended: “They thought they were doing something Christian to baptize us and give us the chance to be better people than our parents. They thought and felt they were saving our lives.”

Church officials in Argentina and at the Vatican declined to answer questions about their knowledge of or involvement in the covert adoptions.

For many years, the search for the missing children was largely futile. But that has changed in the past decade thanks to more government support, advanced forensic technology and a growing genetic data bank from years of testing. The latest adoptee to recover her real identity, Laura Reinhold Siver, brought the total number of recoveries to 105 in August.

Still, the process of accepting the truth can be long and tortuous. For years, Ms. Montenegro rejected efforts by officials and advocates to discover her true identity. From a young age, she received a “strong ideological education” from Colonel Tetzlaff, an army officer at a secret detention center.

Read the full story HERE.

See also the excellent film The Official Story.

NYT

October 8, 2011

Daughter of ‘Dirty War,’ Raised by Man Who Killed Her Parents

By ALEXEI BARRIONUEVO

BUENOS AIRES — Victoria Montenegro recalls a childhood filled with chilling dinnertime discussions. Lt. Col. Hernán Tetzlaff, the head of the family, would recount military operations he had taken part in where “subversives” had been tortured or killed. The discussions often ended with his “slamming his gun on the table,” she said.

It took an incessant search by a human rights group, a DNA match and almost a decade of overcoming denial for Ms. Montenegro, 35, to realize that Colonel Tetzlaff was, in fact, not her father — nor the hero he portrayed himself to be.

Instead, he was the man responsible for murdering her real parents and illegally taking her as his own child, she said.

He confessed to her what he had done in 2000, Ms. Montenegro said. But it was not until she testified at a trial here last spring that she finally came to grips with her past, shedding once and for all the name that Colonel Tetzlaff and his wife had given her — María Sol — after falsifying her birth records.

The trial, in the final phase of hearing testimony, could prove for the first time that the nation’s top military leaders engaged in a systematic plan to steal babies from perceived enemies of the government.

Jorge Rafael Videla, who led the military during Argentina’s dictatorship, stands accused of leading the effort to take babies from mothers in clandestine detention centers and give them to military or security officials, or even to third parties, on the condition that the new parents hide the true identities. Mr. Videla is one of 11 officials on trial for 35 acts of illegal appropriation of minors.

The trial is also revealing the complicity of civilians, including judges and officials of the Roman Catholic Church.

The abduction of an estimated 500 babies was one of the most traumatic chapters of the military dictatorship that ruled Argentina from 1976 to 1983. The frantic effort by mothers and grandmothers to locate their missing children has never let up. It was the one issue that civilian presidents elected after 1983 did not excuse the military for, even as amnesty was granted for other “dirty war” crimes.

“Even the many Argentines who considered the amnesty a necessary evil were unwilling to forgive the military for this,” said José Miguel Vivanco, the Americas director for Human Rights Watch.

In Latin America, the baby thefts were largely unique to Argentina’s dictatorship, Mr. Vivanco said. There was no such effort in neighboring Chile’s 17-year dictatorship.

One notable difference was the role of the Catholic Church. In Argentina the church largely supported the military government, while in Chile it confronted the government of Gen. Augusto Pinochet and sought to expose its human rights crimes, Mr. Vivanco said.

Priests and bishops in Argentina justified their support of the government on national security concerns, and defended the taking of children as a way to ensure they were not “contaminated” by leftist enemies of the military, said Adolfo Pérez Esquivel, a Nobel Prize-winning human rights advocate who has investigated dozens of disappearances and testified at the trial last month.

Ms. Montenegro contended: “They thought they were doing something Christian to baptize us and give us the chance to be better people than our parents. They thought and felt they were saving our lives.”

Church officials in Argentina and at the Vatican declined to answer questions about their knowledge of or involvement in the covert adoptions.

For many years, the search for the missing children was largely futile. But that has changed in the past decade thanks to more government support, advanced forensic technology and a growing genetic data bank from years of testing. The latest adoptee to recover her real identity, Laura Reinhold Siver, brought the total number of recoveries to 105 in August.

Still, the process of accepting the truth can be long and tortuous. For years, Ms. Montenegro rejected efforts by officials and advocates to discover her true identity. From a young age, she received a “strong ideological education” from Colonel Tetzlaff, an army officer at a secret detention center.

Read the full story HERE.

See also the excellent film The Official Story.

2011 Hong Kong Opera Censored By Beijing? Opera Canceled Three Weeks Before Debut

SLATE via the Financial Times

Nixing In China

A Hong Kong opera faces censorship from Beijing.

Posted Sunday, Oct. 9, 2011, at 9:32 AM ET

For months, public structures in Hong Kong have been draped with dreary sepia-coloured banners, some as large as a small building, publicising a new opera about Sun Yat-sen, the father of the Chinese Republic, the architect of the revolution of 1911 that brought down the Manchu dynasty. But the Hong Kong premiere on October 13 of a modern opera about a historical figure had created scarcely a musical ripple in the city, whose attention was turned towards upcoming concerts by the Vienna Philharmonic and a sold-out recital by the pianist Murray Perahia.

Then, on September 30, the Beijing premiere of Dr Sun Yat-sen at Beijing’s National Centre for the Performing Arts was abruptly called off for “logistical reasons”, which pitchforked the issue on to the front pages of Hong Kong newspapers amid a plethora of conspiracy theories. The reasons mooted for the cancellation run from reported complaints by the National Council of Performing Arts in Beijing that the music was either not ready or “too modern” to be performed, to speculation that the love story of Sun and his third wife, Soong Ching-ling, who was 26 years his junior, was too racy for Beijing’s censors. Inevitably, there have also been plenty of hypotheses put forward in this technicoloured soap opera that the political content worried the cultural commissars in Beijing. Although Sun is feted in both Communist China and democratic Taiwan, his life is a minefield of sensitivities for Communist Chinese government censors – not least his support for pan-Asian co-operation with Japan, long seen as an enemy of China, his request in 1923 to the US and European governments to take over China’s provincial capitals to modernise them and his attempt towards the end of his life to curry favour with brutal Chinese warlords.

Read the full story HERE.

Nixing In China

A Hong Kong opera faces censorship from Beijing.

Posted Sunday, Oct. 9, 2011, at 9:32 AM ET

For months, public structures in Hong Kong have been draped with dreary sepia-coloured banners, some as large as a small building, publicising a new opera about Sun Yat-sen, the father of the Chinese Republic, the architect of the revolution of 1911 that brought down the Manchu dynasty. But the Hong Kong premiere on October 13 of a modern opera about a historical figure had created scarcely a musical ripple in the city, whose attention was turned towards upcoming concerts by the Vienna Philharmonic and a sold-out recital by the pianist Murray Perahia.

Then, on September 30, the Beijing premiere of Dr Sun Yat-sen at Beijing’s National Centre for the Performing Arts was abruptly called off for “logistical reasons”, which pitchforked the issue on to the front pages of Hong Kong newspapers amid a plethora of conspiracy theories. The reasons mooted for the cancellation run from reported complaints by the National Council of Performing Arts in Beijing that the music was either not ready or “too modern” to be performed, to speculation that the love story of Sun and his third wife, Soong Ching-ling, who was 26 years his junior, was too racy for Beijing’s censors. Inevitably, there have also been plenty of hypotheses put forward in this technicoloured soap opera that the political content worried the cultural commissars in Beijing. Although Sun is feted in both Communist China and democratic Taiwan, his life is a minefield of sensitivities for Communist Chinese government censors – not least his support for pan-Asian co-operation with Japan, long seen as an enemy of China, his request in 1923 to the US and European governments to take over China’s provincial capitals to modernise them and his attempt towards the end of his life to curry favour with brutal Chinese warlords.

Read the full story HERE.

Thursday, October 06, 2011

Music Professor Stephen Shearson Critiques Ken Burns' Use of Music in his 2011 Prohibition Documentary

The following is an excellent letter Prof. Stephen Shearson faxed to Ken Burns' production company after viewing Burns' new Prohibition documentary. Thanks to Prof. Shearson for permission to repost this, which originally appeared on the Society for American music listserv.

Mr. Ken Burns

Florentine Films

Walpole, NH 03608

fax: (603) 756-4389

Dear Mr. Burns,

Last night I (along with many others, I'm sure) finished watching your documentary Prohibition. It's another very fine and informative production. As a music historian, however, I'd like to provide some feedback about the music used.

You should know first that, when I heard you had used Wynton Marsalis for much of the music, my heart sank. Mr. Marsalis is a brilliant musician, but he's not a brilliant historian, and when you ask him (or Dan Morgenstern, for that matter) a musical question, his answer is likely to be, "Jazz." Thus we had in Prohibition the use of jazz idioms covering almost everything like a smothering blanket. Last night, for example, I kept hearing what sounded like a recording by Sidney Bechet associated with various figures (Al Smith being one) who probably never listened to or, if he did, probably didn't care about Bechet. The musical message of the documentary was that just about everyone of that time listened to and associated themselves with jazz. Not so. Although Fitzgerald labeled the 1920s "The Jazz Age," I think we need to recognize that he was referring primarily to the part of society and the generation that he knew best and that was a very limited group.

I also noticed the absence of any recognizable Temperance songs—-in a documentary about Prohibition. Perhaps you know that American publishers, especially sacred-music publishers, issued numerous collections of Temperance songs in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century. But we heard none of them (that I could tell). Nor did I hear any recognizable gospel songs—and by "gospel" here I refer to the songs published primarily between the 1870s and 1920s by northern and midwestern publishers and written by the likes of Fanny Crosby, Sankey, Doane, Root, etc. These songs were immensely popular and influential in American society, especially among those who supported the Temperance movement. Just hearing a group singing one or two Temperance songs and gospel songs would have added much to our understanding of those who promoted Prohibition. I'm almost certain there are contemporaneous recordings of both.

As someone who self-identifies as a white southerner, I was also sensitive to the music associated with southerners (white and otherwise) and also westerners or midwesterners, such as Willebrandt. All I recall hearing were unimaginative uses of solo banjo and slide guitar or dobro. I recall, at one point, looking at images of Willebrandt while hearing a barely recognizable tune being plunked on a solo banjo and thinking, "This woman probably never listened to banjo music and would have wondered why anyone would have associated her with such." Others you represented in Prohibition would have listened to early country or Old Time recordings; it's very likely that recordings exist in that idiom celebrating both drink and Temperance, but we heard none of those. And you could have represented Teetotaling southern African Americans by some of the highly entertaining recordings of sermons by the likes of the Rev. J. M. Gates.

I could go on in this vein, but here's the bottom line: I think you're an excellent documentarian, and I very much enjoy watching your productions, but you're overlooking a strong resource when it comes to the use of music on American topics. The Society for American Music (SAM) is a thriving professional society of music historians specializing in American music, and I can think of a number of persons you could contact who are very familiar with the music of the nineteenth and early twentieth century—individuals who could help you provide a much-more-nuanced and historically, socially, and culturally accurate set of musical associations. Many of those same people are involved in other professional societies as well, but SAM is probably where I'd start. They, furthermore, have access to or control archives (a la Morgenstern) that can provide recordings of the era.

Please consider these constructive comments as you continue your work in the future.

Most sincerely,

Stephen Shearon

Professor of Music

Mr. Ken Burns

Florentine Films

Walpole, NH 03608

fax: (603) 756-4389

Dear Mr. Burns,

Last night I (along with many others, I'm sure) finished watching your documentary Prohibition. It's another very fine and informative production. As a music historian, however, I'd like to provide some feedback about the music used.

You should know first that, when I heard you had used Wynton Marsalis for much of the music, my heart sank. Mr. Marsalis is a brilliant musician, but he's not a brilliant historian, and when you ask him (or Dan Morgenstern, for that matter) a musical question, his answer is likely to be, "Jazz." Thus we had in Prohibition the use of jazz idioms covering almost everything like a smothering blanket. Last night, for example, I kept hearing what sounded like a recording by Sidney Bechet associated with various figures (Al Smith being one) who probably never listened to or, if he did, probably didn't care about Bechet. The musical message of the documentary was that just about everyone of that time listened to and associated themselves with jazz. Not so. Although Fitzgerald labeled the 1920s "The Jazz Age," I think we need to recognize that he was referring primarily to the part of society and the generation that he knew best and that was a very limited group.

I also noticed the absence of any recognizable Temperance songs—-in a documentary about Prohibition. Perhaps you know that American publishers, especially sacred-music publishers, issued numerous collections of Temperance songs in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century. But we heard none of them (that I could tell). Nor did I hear any recognizable gospel songs—and by "gospel" here I refer to the songs published primarily between the 1870s and 1920s by northern and midwestern publishers and written by the likes of Fanny Crosby, Sankey, Doane, Root, etc. These songs were immensely popular and influential in American society, especially among those who supported the Temperance movement. Just hearing a group singing one or two Temperance songs and gospel songs would have added much to our understanding of those who promoted Prohibition. I'm almost certain there are contemporaneous recordings of both.

As someone who self-identifies as a white southerner, I was also sensitive to the music associated with southerners (white and otherwise) and also westerners or midwesterners, such as Willebrandt. All I recall hearing were unimaginative uses of solo banjo and slide guitar or dobro. I recall, at one point, looking at images of Willebrandt while hearing a barely recognizable tune being plunked on a solo banjo and thinking, "This woman probably never listened to banjo music and would have wondered why anyone would have associated her with such." Others you represented in Prohibition would have listened to early country or Old Time recordings; it's very likely that recordings exist in that idiom celebrating both drink and Temperance, but we heard none of those. And you could have represented Teetotaling southern African Americans by some of the highly entertaining recordings of sermons by the likes of the Rev. J. M. Gates.

I could go on in this vein, but here's the bottom line: I think you're an excellent documentarian, and I very much enjoy watching your productions, but you're overlooking a strong resource when it comes to the use of music on American topics. The Society for American Music (SAM) is a thriving professional society of music historians specializing in American music, and I can think of a number of persons you could contact who are very familiar with the music of the nineteenth and early twentieth century—individuals who could help you provide a much-more-nuanced and historically, socially, and culturally accurate set of musical associations. Many of those same people are involved in other professional societies as well, but SAM is probably where I'd start. They, furthermore, have access to or control archives (a la Morgenstern) that can provide recordings of the era.

Please consider these constructive comments as you continue your work in the future.

Most sincerely,

Stephen Shearon

Professor of Music

Wednesday, October 05, 2011

Misspelled Tattoos 5: To/Too

Oh yes, time for another installment of poor souls who have permanently inked spelling errors into their skins. This post is dedicated to the common error of confusing the words "to" and "too." No big deal in a blog or email, but the skin... well, that's another matter.

[I should mention that the file name on this next photo is "too dumb to spell"]

Another two from Ugliest Tattoos

Check out Ugliest Tattoo, Fail Blog, and WTF Tattoos for more.

For a previous blog post dedicated to misspelled tattoos with the words "your and "you're" click HERE.

For a previous post of misspelled tattoos on the words "Belief" and "believe" click HERE.

For a post on wrong-word tattoos, click HERE.

[I should mention that the file name on this next photo is "too dumb to spell"]

Another two from Ugliest Tattoos

Check out Ugliest Tattoo, Fail Blog, and WTF Tattoos for more.

For a previous blog post dedicated to misspelled tattoos with the words "your and "you're" click HERE.

For a previous post of misspelled tattoos on the words "Belief" and "believe" click HERE.

For a post on wrong-word tattoos, click HERE.