music box

The Faerie Queen

The secret to Enya's success.

By Jody Rosen

Posted Tuesday, Dec. 27, 2005, at 6:06 AM ET

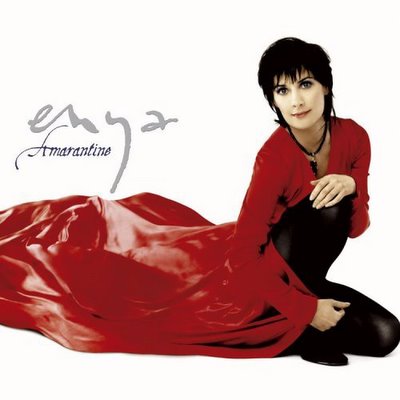

Who is Enya? More to the point: What is she? It's a question you can't help but ask of the 44-year-old singer from County Donegal, Ireland, who, over the past 20 years, has carved a niche as popular music's faerie queen. She's slathered her songs in otherworldly reverb, overdubbed her voice into angelic choirs, and appeared in music videos gliding through mist-shrouded landscapes. When we last heard from her, in 2002, she was crooning songs on the Fellowship of the Ring soundtrack—in Elvish. On the cover of her new album, Amarantine, she gazes out with big dewy moon eyes, wearing what appears to be a spinnaker. Search beneath its billows and you would undoubtedly find a pair of wings and a wand.

Enya may not be of this earth, but she's done rather well here. She began her career in 1980, singing with her brothers and sisters in Clannad, which blended pop tunes and traditional Irish folk music. She left the family band two years later, hooking up with producer/composer Nicky Ryan and lyricist Roma Ryan, the husband and wife who remain her collaborators to this day. The trio worked on film and television scores for several years before graduating in 1987 to proper albums, but those early gigs left their mark. To call Enya's music "cinematic" is an understatement—nearly every song plays like the soundtrack for a majestic film montage, with the camera swooping from lush green valleys to craggy coastlines and upward, zipping past mountain peaks, punching through cloud cover, soaring into the blue and beyond, to touch the face of God, or Gandalf.

On the opening song of Enya's self-titled debut album, "Play MediaThe Celts," this potent formula is already in place. A synth bassline provides a gentle throb; a major key melody swells, crests, recedes, and swells again. Rising over the music is Enya, or rather, Enyas—her voice multitracked into what sounds like a Gregorian choir on helium. The production values have been refined in the years since, with a synthesized string orchestra sound replacing the debut album's garish keyboard gusts. But Enya and the Ryans haven't altered their basic musical template one bit. And why should they? Enya broke through to a mass audience with Watermark (1988) and has gone on to sell 65 million records worldwide. The arrival of Amarantine, currently No. 10 on the Billboard album chart, is a reminder that Enya is one of the savviest operators in the music business and, well, an original. Twenty years ago, no one dreamed that there would be a huge audience for an ethereal female vocalist singing pseudo-classical airs with misty mystical overtones—and Enya remains the genre's only practitioner. No one has even tried to imitate her.

On Amarantine, Enya delivers her usual goods. The mood is worshipful and the tempos stately. There is a great deal of plinking and plucking; Enya is fond of harpsichords (or synthesizer approximations thereof) and, especially, pizzicato, the engine of many of her songs, including her signature hit, "Play MediaOrinoco Flow (Sail Away)." The new album's Play Mediatitle track (and first single) is an Enya song par excellence, with every beat of every measure marked by little string stabs, the singer's voice majestically inflated by reverb and the lyrics a string of fuzzy beatitudes: "You know love is with you when you rise/ For night and day belong to love." The song is insipid and insufferable; it may be the worst thing I've heard on the radio all year. It's also a fiendishly effective mood-piece.

Enya has sold more records than any Irish artist besides U2, and she has leveraged her roots, flavoring songs with uilleann pipes, singing in Gaelic, and gesturing in other ways to Riverdance enthusiasts. But Enya's real musical sources are less Old Eire than High Church. There is a maxim variously attributed to Bob Dylan and Elton John—"When in doubt, write a hymn"—and Enya and the Ryans have written hymns ad nauseam. Their signature trick is the use of multitracking to create the soul-stirring lushness of a full vocal choir. It's a cost-saving measure, for one thing. Why hire a roomful of monks when you can conjure a plainchant choir by simply overdubbing Enya's voice to infinity? The result is a singular sound—unreal, inhuman, spooky, and "spiritual"—perfect for those who desire the mystique of medieval choral music without, you know, the medieval music or the chorus. Naturally, it's impossible to replicate this effect in live performance, and Enya has never mounted a concert tour, which has only added to her air of mystery. Roma Ryan, meanwhile, has made the churchy connection explicit, writing several songs for Enya in Latin.

On Amarantine, though, there's a different kind of linguistic stunt. Inspired by their Fellowship of the Ring experiment with Elvish, Enya and Roma Ryan decided to create their own language, Loxian. I wish I could report that this gambit involves smoked salmon; in fact, it revolves around the more banal topic of extraterrestrials. The Loxians, Ryan told the Guardian, "Are much like us. They're in space, somewhere in the night. They're looking out, they're mapping the stars, and wondering if there is anyone else out there. It's to do with that concept: are we alone in the universe?"

Ryan has written a book about the language, Water Shows the Hidden Heart (also the title of a song on Amarantine), in which we learn, among other things, how to ask a Loxian if he'd like a cup of tea ("Hanee unnin eskan?"). The lyricist claims that it was necessary to invent an alternative language because "some pieces that Enya writes, English will just not sit on." But judging by songs like "Play MediaLess Than a Pearl," one of three Loxian numbers on the new album, Loxian is not appreciably more mellifluous than English or Gaelic or Latin or any of the other terrestrial tongues in which Enya has sung. I suspect other, cheekier motives: an effort to deepen Enya's reputation as a mystic and to tighten her grip on the Hobbit crowd. What's Loxian for "brand extension"?

The truth is, it really doesn't matter what language Enya is singing in. No one is listening to her words; the beginning and the end of her appeal is that big gauzy sound. Even if you hate the aesthetic, you have to respect the craft. Beneath Enya's billowing sonic mists, you can discern the structures and symmetries of classic pop songwriting: the melodic hooks that leap out from every song, the revitalizing excursion of an eight-measure bridge, the triumphal return to the main theme. It all might be perfectly tolerable if it weren't so queasily feather-light. As Enya's career has progressed, and her air-goddess shtick has become more entrenched, the bottom end has disappeared from her songs, to the point where, on Amarantine, there is virtually no bass, no lower-register sounds, nothing to ground the music. Enya would do well to remember that, once in a while, everyone—earthling, Middle-Earthling, and Loxian alike—needs to bang on a drum.

Jody Rosen is The Nation's music critic and the author of White Christmas: The Story of an American Song.

Article URL: http://www.slate.com/id/2133149/

No comments:

Post a Comment