Love of woodworking yields guitars that are Taylor-made

By Frank Green

UNION-TRIBUNE STAFF WRITER

May 23, 2006

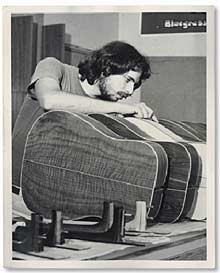

Taylor Guitars president and co-founder Bob Taylor, shown in the final finishing area at the El Cajon factory, has seen the 32-year-old company grow from three employees to 420. SCOTT LINNETT / Union-Tribune

Taylor Guitars president and co-founder Bob Taylor, shown in the final finishing area at the El Cajon factory, has seen the 32-year-old company grow from three employees to 420. SCOTT LINNETT / Union-TribuneBob Taylor has never been one to go with the grain.

While his playmates spent their days on baseball and similar pursuits in the mid-1960s, Taylor was already showing signs of being a woodworking wizard, working with his father to build some of the family's furniture in San Diego's Clairemont neighborhood.

“I was a dweeb, a dork, a wood shop nerd who couldn't catch a ball, didn't have a girlfriend,” remembers Taylor, who won several state industrial-arts awards during his junior high and high school years, including one for fashioning a palm-sized jeweler's vise.

“My dreams came true building things . . . guitars, a desk lamp made out of sheet metal, an ice cream scoop,” he said.

That natural penchant for design and engineering has brought the sweet sounds of success for Taylor, a master guitar maker and co-founder and president of Taylor Guitars in El Cajon.

Taylor, who built his first guitar while in high school, presides over a $62 million company that will produce 67,000 guitars this year. That's up from $45 million and 46,000 guitars five years ago, as a higher percentage of Americans tap into their inner John Mayer.

Taylor guitars range from a $368 basic spruce Baby Taylor to a $12,348 Brazilian rosewood acoustic-electric 12-string.

Among the rock and country music cognoscente who pluck Taylor's elegant, high-gloss acoustic instruments are Prince, R.E.M., Clint Black and Pearl Jam.

“Qualitywise, (Taylor guitars) are universally accepted as top-notch,” said Teja Gerken, gear editor at Acoustic Guitar magazine in San Anselmo.

Jason Mraz, the million-selling singer-songwriter, travels to concerts lugging seven Taylors, including a new nylon-string Grand Concert model with a mahogany back and sides, red cedar top, Indian rosewood overlay and an ebony bridge.

“Other brands tend to change sound when all you hear is just the amplified version of the instrument,” said Mraz, who wrote hits like “Wordplay” in his bedroom at home in San Diego. “So when it comes time to perform, I want the guitar to sound as intimate as it does at home.”

Taylor, tall and bespectacled, reminisced recently in his office at the company factory off Gillespie Way. He was dressed as he is on most workdays in T-shirt, jeans and running shoes.

Taylor, born in Oakland to a Navy family struggling to pay the bills, settled in San Diego in 1964 when he was 9 and beginning to show talent as a wood and metal craftsman. As a boy, Taylor also was curious as to how model locomotives and other machines functioned.

“He got a clock once and took it apart to see how it worked, then put it back together perfectly,” said Dick Taylor, his father and a woodworker himself. “Bob didn't like sitting around watching TV or reading. He liked building things.”

Taylor tried to build his first guitar when he was in the fourth grade, using one he'd bought from a friend for several dollars. He ended up sawing off the guitar neck in an attempt to build a better model.

Later, Taylor would watch boyhood friend Michael Broward play guitar in his garage across the street. “I'd plug in my amp, stand next to the washer and dryer and play to the songs on the radio, like 'I'm Henry VIII, I Am,' ” said Broward.

Taylor subsequently took guitar lessons from a teacher who came to the Taylor home and tutored him on a low-end guitar bought at Fedmart.

He didn't get serious about constructing an instrument from scratch until his junior year in wood shop at Madison High School. “I'd seen an EKO 12-string guitar in a music store window, but couldn't afford it,” Taylor said.

Armed with the book “Classic Guitar Construction” presented to him by his wood shop teacher, he proceeded to build three guitars during the next two years.

The construction quality got him a job at a Lemon Grove guitar factory upon high school graduation in 1973. It was a somewhat unlikely job for Taylor, a religious man who's also politically conservative.

The facility, American Dream, was “a hippie shop. . . . If you hung out, you got a work bench,” Taylor recalled.

It was there that Taylor first met Kurt Listug, who would become his longtime business partner. The two and another investor bought the shop in 1974 with $10,000 raised from family members and friends.

Bob Taylor, who founded Taylor Guitars with Kurt Listug and another partner in 1974, inspected a group of Dreadnought guitars in the El Cajon company's early days.

Building guitars was one thing, but learning to market them took years of trial and error. For the first several years, the company barely sold enough instruments to keep the spray paint machines running.

“When I first met him, he was eating tomato soup out of a can. . . . He was not making any money,” said Cindy Taylor, who's been married to Taylor for 28 years.

Listug often would go on the road to persuade music stores to carry the guitars, while Taylor minded the store. “I was hand carving guitars from 7 a.m. to midnight for three to four years,” said Taylor, who also found time to play up to four concerts a week in a Christian music band.

One of the first signs that all the hard work was being appreciated came with the release of Neil Young's concert documentary “Rust Never Sleeps” in 1978. On the big screen was the folk-rocker playing a Taylor.

Other indirect endorsements came in the early '80s from the Eagles' Glenn Frey and rocker David Crosby, who was quoted as saying, “I didn't buy two (Taylor guitars) by accident.”

Taylor Guitars entered a higher level in the mid-1980s when funk-rock star Prince began playing a Taylor in the artist's trademark purple. It was during this period that Taylor fashioned a green guitar for the cover of a Christmas album by country rockers Alabama and a red guitar for Sammy Hagar.

Taylor guitars were in vogue, if not yet too hot to handle.

Today, Taylor Guitars employs 420 at its El Cajon factory and a new factory south of the border in Tecate. The Tecate facility provides woodwork support for the firm's entry-level guitars and for guitar cases as the company battles lower-cost – some say lower-quality – manufacturers in China and elsewhere.

The factory “is the answer for the mid-price guitar market,” said Taylor. “If Tijuana and Tecate are doing well, that's good for San Diego.”

Taylor Guitars competes in the $7.5 billion instrument industry with such companies as Nazareth, Penn.-based Martin Guitars, whose client roster includes icons like Bob Dylan and Joni Mitchell.

Taylor and Martin “have a good relationship and friendship, even if there is more than healthy competition,” said Martin spokesman Dick Boak, noting that his larger company will have revenues this year of nearly $90 million and produce about 90,000 acoustic instruments.

“It's not uncommon for our employees to take a tour of their factory, and vice versa,” he said.

Taylor, who's hand-carved hundreds of guitars over the years, remains an active woodworker – but rarely touches a headstock or guitar neck. The production of Taylor guitars is now mostly accomplished via computer-programmed milling machines that render accuracy of better than .0005 of an inch, while the wood used to connect neck and bottom is likewise formed to machine specifications.

“I love this technology and do not regret going toward it,” said Taylor, noting that nearly every guitar factory has followed his lead over the years. He partly attributed the easy transition the company has made to sophisticated tooling machines to industrial arts classes he took in high school.

“Machines have never scared me, whereas many luthiers have never really worked with machines, as they approached guitar making from an arts-crafts point of view,” he said.

Taylor often retreats to his wood shop near the factory; it's equipped with high-end table saws, sanders and other equipment. His current project is building a walnut desk for his office.

He attends weekly services at Skyline Wesleyan Church in La Mesa with his wife and until a recent break had played guitar at services for 20 years.

“I've never lapsed,” said Taylor. “I made up my mind about (religious) things early, and I live my life accordingly.”

The couple recently bought a $700,000, 10,000-square-foot house in Indiana to accommodate up to four missionary families who need rest from religious work in Croatia and other world hot spots.

The Taylors' daughters are on their own now: Minet, 25, works at Neiman Marcus, and Natalie, 20, is a student at Vanguard University in Costa Mesa.

If Taylor has a pet peeve, it's the demise in the public school system of industrial arts programs like the ones he thrived on as a youngster. Part of the problem has been the trend to focus on academic study programs tailored for precollege work, he said.

The company has tried to do its part to keep musical interests alive in children by donating more than 1,000 guitars to area school districts in the last five or six years.

Taylor's next project will be overseeing construction of a new Rancho San Diego home, an Italian courtyard-style residence that could cost up to $4 million. In addition to 6,000 square feet of living space, the floor plan includes a 2,000-square-foot quilting room.

And, of course, a 2,500-square-foot wood shop.

No comments:

Post a Comment